|

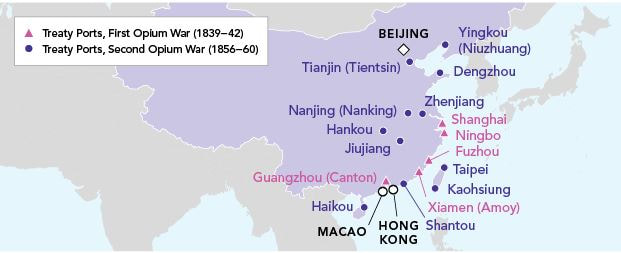

By: Ben Clark The 1950s and 1960s were the heyday of big budget, adventure-historical dramas. Thus, we had Dr. Zhivago, Ben-Hur, Zulu, Lawrence of Arabia, El Cid, The Alamo, The Warlord, Julius Caesar, The Blue Max, Battle of Britain, Khartoum, and Spartacus – to name a few of my favorites. My guess is that if you like some of these movies, you'll like 55 Days at Peking (1963). The movie is based on the true story of the 1900 Boxer Rebellion in China during the Qing Dynasty. Before this 1963 film, Hollywood mostly ignored Chinese history and culture, and pitifully few round-eye English speaking people took even a casual interest in Chinese history. 55 Days at Peking is the first major film to examine the clash of Western and Chinese cultures, and is still relevant to this day when trade and political tension with China is a prominent, almost daily, American news story. One of my objectives is to determine just how fair and truthful the movie presents the actual events. With that in mind, I'd like to begin by summarizing the historical arc of the early Chinese/ European / American foreign relations to put the movie into historical context and correct some confused comments I have read on the internet about the setting, or historical background, of the movie – 55 Days at Peking. Chinese – European trade begins Europeans did not arrive in China in any real numbers until the 16th century, so let’s begin there. As was so often the case of early sea exploration, it was the 16th century Portuguese explorers and navigators who founded and established the nautical trade routes to India and China. In 1557, the Chinese Ming Dynasty (1368-1644) leased the territory of Macau to Portugal. The Macau trading post became the accepted model for foreign trade in China. News of the profitable trade with the Orient spread like wildfire, and worldwide trading competition began in earnest. Soon the English, Spaniards, and Dutch discovered new sea routes to Chinese port cities. By 1773 the British East India Company had penetrated the Chinese market and became the leading merchants of the China trade, overtaking the Portuguese. The English East India Company was buying tea, porcelain and silk from China for sale in England and Europe. As tea became a popular English drink, the tea trade became more and more important. In 1785, about 15 million pounds of tea was being imported into England. China, in particular the Qing Dynasty, was getting rich on British silver. Opium Wars 1839-1842 & 1856–1860 At first, the Manchu Emperors (aka Qing Dynasty) permitted free trade with foreigners, mainly British and other Europeans, so long as the foreigners were kept isolated. No foreigners were permitted in Peking, the seat of the Qing Dynasty. The British were strictly limited to live in a small enclave in the city of Canton, they could not bring their wives, and they were barred from learning Chinese. Canton was a major terminal on the fabled Chinese Silk Road and is about 75 miles north of Hong Kong on the Pearl River. Note: The Chinese changed the name of Canton to Guangzhou, as was the trendy anti-colonial sentiment in the 1960s. The British merchants (and Britain was the world's greatest trading nation) found the restrictions chafing, irrational, primitive and of course profit-reducing. There was little demand in China for British finished goods, but British merchants soon found a product for which there was enormous Chinese demand – opium. So in order to help balance the trade deficit, the British set up a trade triangle with India and China. India provided abundant, cheap opium for the British to trade in China for silk and tea to sell in Europe at enormous profit. The Manchu Emperors banned opium; however, the ban was not enforced. Opium smoking dens popped up all over China. Many officials turned a blind eye toward the opium trade since they collected heavy import taxes on all foreign trade. An upper class Chinese opium den 1830 Eventually internal pressure from reformist groups in China caused the Manchu Emperors to act forcefully against the opium trade. In 1839 Chinese warships blockaded Canton and demanded the British hand over 20,000 opium chests for destruction. The British decided to fight instead of complying with Chinese demands. The Manchu rulers were entirely ignorant of how ineffective the primitive Chinese navy and shore batteries would be against the British Navy - who swiftly crushed the Chinese forces and took command of the important coastal regions of China. British warships smash Chinese blockade at Canton The First Opium War ended with the Nanjing treaty of 1842 which ceded Hong Kong Island together with its superb deep water harbor to the British. Also the treaty opened up the interior of China for Christian missionaries to travel, proselytize freely and establish missions all over China. A Second Opium War flared up in 1856 and once again the Qing Dynasty was defeated when British and French infantry captured Peking, forcing the Emperor to flee the royal palace and sue for peace. The emperor’s Summer Palace outside Peking was burned to the ground on orders by British commander Lord Elgin, “To punish the [Qing] court while sparing the people.” In the peace treaty of 1860, China ceded the Kowloon Peninsula to the British. Kowloon, being directly adjacent to British ruled Hong Kong Island, further increased British influence in a strategic location. The “Forbidden City” Peking was also opened to foreigners. The rules were relaxed to allow foreign embassies. For the next century, China would be subject to further invasions and “unfair” treaties, which ended only with the termination of special western rights in China in 1943 under Chiang Kai-shek (not under Mao in 1949, as the Chinese Communist propaganda claims). The peace treaties proved disastrous to China's exclusionary trade policy. China opened up four, and then nine, separate enclaves within key coastal cities (the "Treaty Port or Concessions") for westerners to live with their families, and police themselves within the enclaves under their own laws, and, of course, continue the opium trade with far more access to Chinese cities. Meanwhile, other nations such as the U.S., France, Germany, Italy, and Japan all began to compete with Britain in trading with China. The China trade became one of the great careers for Americans seeking adventure and juicy profits. The "China Clipper" ships built in the U.S. became world-renowned - as did the courage and skill of their crews. America soon began to out-strip all other nations in sending missionaries to China. Throughout the U.S., churches raised money to support the Chinese missions where the congregants were assured the missionaries were doing God's work. And in fact, millions of Chinese were converted to Christianity and benefited from local charity provided by the missionaries. THE CHINESE SON OF GOD and the Taiping (aka Heavenly) Rebellion 1850-1864  While the opium war itself had a direct impact on relatively few Chinese, one of the results of the opening up of China, demanded by the 1842 treaty, was the influx of thousands of Christian missionaries throughout China. The religious impact on China took a tragic turn when a charismatic lunatic, Hong Xiuquan, converted to Christianity and after a series of hallucinations and dreams, became convinced that he was the Chinese Son of God. Hong soon had thousands of followers chanting the 10 Commandments in Chinese. The new converts took up arms and formed the Taiping Heavenly Kingdom Army to defeat the Demons plaguing China. In 1850 Hong declared that the Demons were in fact the Qing Dynasty. Imperial forces and Hong’s Taiping army clashed in 1851, and the Taiping army was victorious in the first series of battles. Inspired by success, Hong’s forces went on the offense and gained control of the critical Yangzi River Valley. The Taiping army captured Tianjin and also took Nanjing, a major city of 2 million. After an attempt to seize Peking (Beijing) failed, Hong chose to cease conquest and fortify his forces around Nanjing. For the next 11 years Hong’s army held Nanjing and the surrounding territory. European forces in China decided to aid the Qing Dynasty in seizing back the lands held by the Taiping army. In one of the bloodiest civil wars in world history, Imperial forces, often commanded by British officers, finally beat back the Taiping army to Nanjing. The British Major Charles Gordon won 33 battles in a row and became the Emperor’s Golden Boy. Unlike the Chinese Imperial generals who favored massed frontal assaults, Gordon was highly successful defeating much larger forces using maneuver, steam powered gunboats and surprise. Forever after he was known as “Chinese Gordon” (see photo to the right). The siege of Nanjing lasted several months until resistance collapsed when Hong was found dead in May 1864. The Imperial Army entered the city and massacred Hong’s followers. Estimates vary but the Taiping Rebellion is believed to have claimed at least 20 million dead, and some estimates range as high as 70 million killed. Sino–Japanese War 1894–95 & Russian concessions in Northern China Above is a famous French political cartoon from 1898. A pastry represents "Chine" (French for China) and is being divided between caricatures of Queen Victoria of the UK, Kaiser William II of Germany (who has planted his knife into the pie), Tsar Nicholas II of Russia, the French Marianne, and a Japanese samurai. In the background a Qing official throws up his hands to try and stop them, but is powerless and ignored. It is meant to be a figurative representation of the Imperialist tendencies of these nations towards China during the decade. Noticeably absent from the group is the United States. By the late 19th century, Russia and Japan sought to carve areas out of the obviously weak Chinese Qing Empire. In 1895, Japan crushed China in a short but fierce war - and seized Chinese Imperial territories of Korea and Taiwan. The Japanese also obtained railroad and industrial licenses in Manchuria. Not to be outdone by the rival Japanese, Russia invaded Outer Mongolia and demanded concessions in northern coastal China, in particular ice-free Port Arthur and Talienwan Bay on the Liao-Tung Peninsula of Manchuria. After a Russian battle fleet appeared in the Port Arthur harbor, the Qing Dynasty reluctantly agreed to a 10 year lease of Port Arthur and adjacent territories in Manchuria. The Russians immediately began building a rail line linking Port Arthur to the Tsar’s military base at Mukden. The Russians also began fortifying Port Arthur, indicating they had no intention of ever leaving and returning the port to China. The British and other European nations failed to object - but the U.S. reacted strongly to the foreign incursions - and Secretary of State John Hay pronounced the "Open Door" policy, insisting that no nation should obtain territorial advantages or further exclusive concessions in China. Popular sentiment in America was fiercely pro-Chinese and against the Japanese and Russian invaders. Japan was finally forced by the American-led western powers to return some of its territorial gains from the war. Rise of the Boxers The loss of the wars and foreign domination was obviously a great humiliation to the Chinese people who had always regarded China as the center of the universe (the "Middle Kingdom") and their emperors as appointed by Heaven to rule the earth. The fast growing Western and Japanese influence aroused hostile feelings among many Chinese toward the Christian religion and its missionaries, associating such "foreign" culture with Chinese humiliation at foreign hands and resenting the very implication from the missions' existence that the Chinese were backward and must be taught by the foreigners. Under these circumstances by the late 1890’s, a Chinese secret organization called the Society of the Righteous and Harmonious Fists (nicknamed Boxers) began regular attacks on foreigners and Chinese Christians. The Boxers were a fanatical and murderous semi-religious sect (somewhat like the Mahdi's Dervishes in Sudan or the Wahabbi sect of Islam that bedevils the Saudis today). They swore to kill all the foreigners and to drive them out of the country. They were in no sense a positive force - merely a fierce and frenzied organization of hate for the West and all its ways. Throughout the 1890s the Boxers grew in strength and became more violent. The Boxers' often targeted missionaries and the Chinese Christian converts -- they were defenseless and located throughout the country. The massacres of missionaries and an estimated 30,000 converts aroused outrage back in the U.S. and Britain. Boxers also burned Russian railway stations on the strategic Mukden to Port Arthur line; thereby, giving the Russian Tsar an excuse to send 200,000 troops to Manchuria. The Western legations in Peking began to evacuate as many missionaries as possible and attempted to persuade/threaten the Qing Dynasty to put down the rebellion with the Imperial Army. And so our movie begins! 55 Days at Peking 1963 action adventure history This movie is based on a true story and is dramatically presented with fairly accurate history, per Hollywood standards. Surprisingly the sets and costumes are all credible even though the movie was filmed in Spain. In 1963, the Peoples Republic of China (PRC) was isolated and locked down behind the Iron Curtain. Also keep in mind only ten years past, the US-led UN military force and the PRC fought a bloody, bitter war of attrition in Korea. The studio succeeded in gathering an impressive number of Euro-Oriental actors for the battle scenes, and also managed to obtain some authentic Qing Dynasty wardrobes for the actors playing the royals. The opening scenes welcome the audience to 1900 Peking (now Beijing), China. In a large walled compound in the heart of Peking, are located the foreign embassies with economic interest in China. The United States, England, France, Italy, Germany, Russia, Austria, and Japan are all represented. Next we see the star, Charlton Heston (Major Lewis) riding horseback and leading a company-sized column of US Marines into the city (the western powers were each allowed a small scale military force for security). In a key scene, we are introduced to the Boxers when Major Lewis notices a man being tortured and drowned on a water wheel by Boxer thugs. We later learn that the victim is a British priest. Lewis bargains with the Boxers to release the priest, and pay $20 in gold if the man is still alive. He is dead. A violent exchange follows and one of the armed Boxers is killed by the marines. Major Lewis flips the $20 gold piece to the lead Boxer and defuses the tense situation. General Jung-Lu warns the Empress Another key scene introduces Empress Tzu-hsi and the royal Mandarin court. A heated conversation between Chinese Prince Tuan (pro-Boxer) and General Jung-Lu concerning the Boxers displays the split in the Chinese court between those who believed the Boxers are “useful idiots” who could throw out the foreigners and restore China's pride - and those who believed that if they sided with the Boxers and lost, the western nations would themselves take victorious action and the Manchu court would wind up paying a high price in further concessions and reparations. As depicted in the film, the full scale Boxer Rebellion is sparked by the vicious attack on the German Ambassador as he rides in his carriage, not far from the Embassy Compound. In a shocking scene, he is dragged to the ground and clubbed to death by the Boxer mob (in real life, both the Japanese and German Ambassadors were killed by Boxers in June 1900). Major Lewis is witness to the attack and notices Prince Tuan directing the mob with hand signals. The British Ambassador Sir Arthur, brilliantly played by David Niven, immediately demands an audience with the Chinese Empress to formally protest the murder of the German official. He is joined by Major Lewis. The scene in the throne room is magnificent – all the pomp and ceremony you would expect. Sir Arthur receives a tongue lashing by the Empress as she rejects his protest. The result of the meeting is clear: the Empress has decided to back Prince Tuan and not mobilize the Imperial army against the Boxers. She will not protect the foreign compound and urges them to leave the city within 24 hours. Of course the foreigners do not leave (or else there is no reason for the movie). In the critical scene discussing “leave or stay” David Niven (Sir Arthur) steals the show as a true Big-Picture leader who rises to the occasion with a steady hand and precise risk analysis of a very tense and dangerous situation. He convinces the other Ambassadors to stay and band together. Actual history proved Sir Arthur to be correct. It would have been suicide to leave the walled compound. Sir Arthur sends for a military relief force, and makes plans with Major Lewis to defend the compound. The British relief force will have to march 70 miles through hostile territory to reach Peking. No one knows how long they will have to hold out (hint: 55 days is a good guess). The battle scenes that follow are spectacular, and some of the best ever filmed. I can’t understand why this film didn’t do better at the box office and awards season; it’s one of the most ambitious, visually stunning, well done historical epics I’ve ever seen. The film is not without critics who are quick to point out some problems with the casting and the not-so-subtle pro-colonial message. Without treading too far into the dreadful PC minefield, it is fair to say the casting was somewhat marred by the absence of actual Chinese actors in the main characters. Instead we see British and Aussie Anglos dressed in Chinese gowns. This imparts a Euro-centric flavor to the film that was very common for the era. But back in 1963, given the lack of Chinese-American box office stars and Cold War hostility, this cast is the best we can hope to get. Prince Tuan (Robert Helpmann) & Qing Empress Tzu-Hsi (Flora Robson)  The movie has a decided European perspective, and while it justly celebrates the heroism of the vastly outnumbered western defenders, there is an overall willing amnesia about the negatives of imperialism and the opium trade. Compared to the violent Boxer mobs, the imperialists depicted in the movie are quite noble and courteous, not to mention that Heston, Eva Gardner and David Niven were all glamourous Hollywood stars and just had to be the “Good guys”. And this movie has a typical “Good vs bad” theme. C. Heston, Ava Gardner, and David Niven The official viewpoint by the Chinese communist party of the Boxer Rebellion has a completely opposite twist. For example consider this quote by Mao Tse-tung: “Was it the Boxers organized by the Chinese people that went to stage rebellion in the Imperialist countries of Europe and America, and Imperialist Japan to commit murder and arson? Or was it the Imperialist countries that invaded our country to oppress and exploit the Chinese people?” To put it another way, the Boxer Rebellion was an organic uprising by the common Chinese people who are excused from any violence because they can respond, “we live here.” What Chairman Mao glosses over here is the tens of thousands of innocent Chinese slaughtered at the hands of the Boxers. Of course, why would this upset the Chairman? He slaughtered innocent Chinese by the MILLIONS. To quote John Derbyshire, an old China expert, “If there is a prize awarded in hell for murdering Chinese people, the easy winner for the 20th century division is Mao Tse-tung. All this is forgotten in the fixation on foreign wickedness. A well-adjusted Chinese citizen is expected to have "moved on" from the horrors of Maoism (1949-76) but to be fuming with indignation at the Opium War (1839-42).” And so we leave 19th century China, drenched in blood and pyscho-active drugs, and still ruled by the backward, confused Manchu Qing dynasty. The Qing stumbled along for another decade before a (mostly peaceful) transfer of power to the Chinese Republic in 1911. Perhaps the only positive spin about the Boxer vs Western clash is that it hastened the demise of a chaotic, fossilized form of government (the dynastic monarchy) to be replaced by a Chinese Republic. In 1788 after the American constitution was ratified, someone asked Mr. Ben Franklin what type of government do we have now? Franklin, one of the key founders, replied, “A republic, if you can keep it.” Wiser words were never spoken. Unfortunately a Chinese Ben Franklin did not exist. One final comment – I recently bought the 55 Days at Peking DVD. It is of superior quality – both picture and sound. The colors are vivid and the Dolby digital 4.0 surround sound is great. I doubt that Criterion could have done a better job. Language spoken is English, with optional Korean and Japanese subtitles. My copy was made in Korea by DVD Video. I have been disappointed by many vintage film transfers to DVD, but not this one. Source material for this article & Recommended reading list on Chinese history. Hungry Ghosts by Jasper Becker – includes the incontrovertible conclusions how the Maoist policies on agriculture reform resulted in severe famine and 30 million Chinese peasant farmers starved to death. The Chairman's New Clothes & Chinese Shadows by Simon Leys – reveals the horror that was the Mao-driven Cultural Revolution and describes in detail the vast destruction of all that was good and beautiful in China in 1972. The Dragon and the Foreign Devils by Harry Gelber – a scholarly work on the ebb and flow of foreign trade with China extending back to the ancient Silk Road. The Chinese Looking Glass by Dennis Bloodworth - The author, a British journalist who married into an old Chinese family, interweaves his personal experiences in Asia (mostly Hong Kong and Singapore) with a discussion of the history, culture, and present situation of the Chinese people and the factors that have formed the Chinese character. China in Convulsion by Arthur Smith – the author was an American missionary to China during the Boxer Rebellion and altogether spent over 50 years living mostly in small villages in China. This is his detailed eye witness account of the event as he, his wife and 22 other missionaries took refuge in the Peking foreign legation compound in June–August 1900 during the famous siege. Same author also wrote – Chinese Characteristics in 1894, and this became his most famous work. Modern day expats still consider this to the bible for better understanding the Chinese mindset. What’s Wrong with China by Rodney Gilbert – written in 1926 by a Victorian Brit expat, this is the most un-PC account of Chinese characteristics and viewpoint of life in China. Available on Internet Archive. The Opium War by Peter Ward Fay – A detailed narrative of the India-China-England opium trade triangle, and the military campaigns to settle disputes.

1 Comment

|

AuthorWritten and edited by Ben Clark. Copyright 2016-2022. All rights reserved Archives

October 2021

|