|

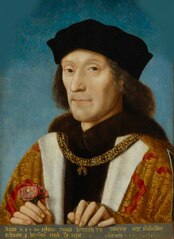

Part 1: The rise of England to World Power (1485-1820) Written by Ben Clark I begin down the lengthy path of English history with a short-cut to the English Renaissance and Age of Exploration. Thus I skip over centuries of ancient and medieval history to focus on the most relevant, and interesting events that shaped and guided the European migration to North America. There is no denying that the political, economic, scientific and cultural influence of the Mother Country on America is important and significant. My wife and I enjoy watching Hollywood and BBC productions of historical dramas set in Merry Olde England. And that could be the real reason I charged down this rabbit hole. One difficulty in composing a narrative covering a huge time span – over five centuries in this case – is to decide how to present the subject matter. For the sake of clear presentation, and format, I used a Monarchy timeline that divides up the various eras into digestible bites, and provides insight into how much and how often the problem of succession-of-power drives British history. Of course, I also include the non-royal players that are well known and sometimes more powerful than the King or Queen. No matter what sovereign sat on the throne, the Industrial and Scientific Revolutions marched ahead; grandma-slow at the beginning then gradually gaining speed and shifting into high gear. Highlights of these two peaceful revolutions are included for a better understanding of the various time periods. Finally to round out the story of each time period, I included some literature highlights for a glance at the cultural influence. The military component of history cannot be ignored especially in the case of British history. This is not meant to be a military history with detailed battlefield tactics, but rather is more of a strategic overview of the warfare with a close look at the British leadership to gain a more human experience as opposed to weaponry analysis or numbers games of divisions and regiments. I skip over some wars which were not a factor in British-American foreign relations, e.g., I still don’t know what all the fuss was about in the Crimean War. This essay is spirited by my passion for history which I have studied since childhood. If you are looking for an axe-grinding rant against Imperialism, slavery, capitalism or anything anti-white then you have blundered to the wrong website. To my British readers, I promise not to crow too much about the American Revolutionary War. The Tudors  Henry VII (1485-1509) ended the bitter War of the Roses. This Warrior-King was crowned on the bloody battlefield of Bosworth Field after the notorious Richard III was killed. Married Elizabeth of York, and so united the two warring houses, York and Lancaster. With social order restored at home and peace with the European Continental powers, England prospered as never before. The King was able to rebuild the royal wealth that was devastated by long, costly wars. He encouraged exploration and sent Cabot and others on expeditions in search of sea trade routes. Henry VII’s court included many exceptional men; chief among them were the likes of Richard Fox and Thomas Lovell. Many historians consider Henry VII the first Renaissance Monarch of England.  Henry VIII (1509-1547) is infamous for having six wives – divorced, beheaded, died, divorced, beheaded, survived... English church split from Rome and Henry declared himself head of the Church of England. The controversial decision was radical and sowed the seeds for future religious tensions and instability. On the continent, the Protestant Reformation came to a full boil with Martin Luther and John Calvin leading the reformists. Popular legend has it that on October 31, 1517 Luther nailed a copy of his 95 Theses to the door of the Wittenberg Castle church, thus beginning the Reformation. Luther also translated the Latin Bible into German, and together with the Gutenberg printing press, copies were available to the public for the first time. It was really a revolutionary idea, for its day. Edward VI (1548-1553) and “Bloody” Mary (1553-1558). Edward was the weak, sickly son of Henry 8 who died young and the crown passed to his sister, Mary. She was daughter of Henry 8 and Catherin of Aragon, a devout Catholic. Mary’s marriage to the Catholic prince Philip of Spain, and the execution of Lady Jane Grey, her Protestant cousin, frightened the royal council. Then the burning of heretics began in 1555 at Smithfield. Mary tried to force Catholic faith back on the English using a few Spanish inquisition methods that were very unpopular in England. During her 5-year reign she ordered 280+ Protestants burned at the stake for their sincere beliefs. The fires of Smithfield, England became synonymous with tyranny and cruelty. In 1588 Mary thought she was pregnant. Her imagined baby was actually a tumor. She was dead before year end. Few mourned her passing.  Elizabeth I (1558-1603) was daughter of Henry VIII and Anne Boleyn. She proclaimed the Church of England as the national religion and rejected the Roman Catholic Church. As queen she cooled religious fanaticism; thereby, improving social stability. She also continued her father’s strong financial support for the Royal Navy. Francis Drake sailed around the world in 1580. Spanish-English relations are strained when British buccaneers plundered Spanish treasure ships sailing from the New World. King Philip of Spain plots to overthrow Elizabeth. Elizabeth executed her Spanish-friendly rival Mary Queen of Scots in 1587 for treason. Mary was from the Catholic House of Stuart, so the execution enraged Philip of Spain. He declared war on England and ordered the military to build an invasion Armada. The luckless Spanish Armada was defeated in 1588. The British East India Company chartered 1600 with a monopoly on British trading and governorship of British controlled territory on the Indian subcontinent. The Company would enjoy the monopoly trade and control until 1857. English literature and theater bloomed. William Shakespeare was at zenith of his popularity. “The Virgin Queen” died childless and unmarried; thereby, triggering a deluge of questionable dynastic claims to the vacant throne. Had she invoked the ancient Roman practice of adopting the most able heir, regardless of family trees, she would have saved her people from several lost decades of strife and bitter fighting. Like her Grandfather Henry VII, her court included a corps of wise and strong advisors: Drake, Raleigh, Hawkins, Essex and the Cecil brothers. Any of these men would have made a sterling king. Crown passed to House of Stuart. The Stuarts  Pilgrims & Indians at first Thanksgiving. Pilgrim folklore still looms large in American mythology. Pilgrims & Indians at first Thanksgiving. Pilgrim folklore still looms large in American mythology. James I (1603-1625) is best known for his most famous and lasting legacy: The King James Bible. In 1604 he gathered a committee of 54 translators and revisers made up of the most learned men in the nation to complete a revised English Bible translation from original Latin manuscripts. By 1610 the King and his scholars agreed on the final translation. The King James Edition of the Bible was published in 1611 by the King’s Printer. The most striking characteristic of the new Bible is its simplicity. It was written with resonance and uplifting rhythms, and easy to remember. The King James Bible has contributed 257 phrases to the English language, more than any other single source, including the works of William Shakespeare. Expressions such as “a Fly in the ointment”, “thorn in the side” and “Do we see eye to eye”, which are still commonly used today, all originated in the King James Bible. New World migration from England to America increased in pace. In the winter of 1620 the Pilgrims sailed the Mayflower into what is now known as Cape Cod Bay, and established Plymouth Colony, directly south of Boston. Two other important American colonies, Virginia and Carolina, were chartered early in the reign of James. Tobacco farming soon made the new colonies an economic success. Catholic king Charles began suppressing the Protestants and especially Puritans. In 1629 large-scale Puritan migration began to Boston and sprawled into the Massachusetts Bay Colony. Charles I (1625-1649) was an inept king and was failed by senior advisor, the Duke of Buckingham. Buckingham was a belligerent war hawk and stumbled into disastrous attacks on Spain and Holland during the religious bloodbath of the Thirty Years War (1618-1648) on the European continent. As was the political custom of the day, when the king needed money in excess of his comfortable allowance and trade tariff fees, Parliament was called into session. To pay for the military fiascos, Charles was forced to summon Parliament over and over. Each time, Parliament became less cooperative and more hostile to an expensive, unbridled royal foreign policy. Parliament raised an army and rebelled against the Royalists. Civil war broke out in 1642 and lasted four years. The Battle of Naseby in 1645 was a great victory for the Parliament army led by Oliver Cromwell. Charles fled the battlefield and was eventually captured, imprisoned and beheaded in 1649. The unstable society under Stuart rule led to mass migration of Puritans and Scots to America. This wave was followed by a similar exodus of upper class nobles during the Commonwealth period. While the Puritans immigrated to northern colonies and Boston, the majority favored the more central colonies, in particular Virginia which expanded in population and power. The Commonwealth (1649-1660). Monarchy abolished and Commonwealth declared in 1649. Oliver Cromwell tried and failed to establish a new dynastic monarchy. Oliver Cromwell died in 1658 and his son, Richard, lasted 9 months in power before being skidded by the army. The crown was offered to the Stuart line. The Stuart Restoration  Charles II (1660-1685) was best known for openly keeping 13 (or more?) mistresses. A British noble wrote this popular ditty about him: Restless he rolls from whore to whore. A merry monarch, scandalous and poor. The Merry Monarch’s truly significant, lasting, and surprising legacy was his patronage for science. In 1662 Charles granted a Charter to the Royal Society of London, making it the first national institution devoted to the promotion of science studies using the “Scientific Method” as determine by Francis Bacon. The Bacon Method required planned, well documented and repeatable experiments. Charles in effect planted the seed for British world leadership in the Scientific Revolution for the next two hundred years. In May 1662 Charles married Catherine of Braganza, daughter of the king of Portugal. As a result of Catherine’s dowry, England acquired a trading post at Bombay, India which would develop into a key base for the future British Empire in India. In 1664 the English took over the Dutch settlement on Manhattan Island and renamed the colony New York. New Amsterdam was renamed New York City. In return the English agreed to transfer a spice island to Dutch control. New York City, with its excellent deep water harbor and access to the Hudson River basin fur trading business, rapidly expanded in population and wealth. The years 1665 and 1666 were indeed unlucky for Britain. A nasty plague was followed by the Great Fire of London. Charles is to be commended for hiring top architects Christopher Wren and Robert Hooke to propose rebuilding plans. The king forbid private rebuilding using wood. The city was rebuilt with brick and stone. Wren’s plan was selected, laying out a new street pattern that still exists in London to this day. Wren also designed the building of 50 new churches, including the sublime St. Paul’s Cathedral. In 1681, King Charles II gave William Penn, a wealthy English Quaker, a large land grant in America to pay off a debt. Penn, who had been jailed multiple times for his Quaker beliefs, went on to found the new colony of Pennsylvania as a sanctuary for religious freedom and tolerance. King Charles II fathered no legitimate heir to the throne, but of his many illegitimate children he favored the eldest, James, awarding him the dukedom of Monmouth. In 1679 Monmouth was appointed to command an English army sent north to quell a Scottish rebellion. He was ruthless and successful in battle. At age 36 he returned to London as the conquering hero. Needless to say, Monmouth got a big head, which would lead to trouble with Uncle James, the next king. James II (1685-1688). James, the younger brother of Charles II, was crowned at age fifty-two. The royal transition was marked by widespread acceptance despite the new King remaining openly loyal to the Catholic Church. He promised to rule with restraint and moderation. Duke Monmouth, the former king’s bastard son, misjudged the popular mood and foolishly launched a rebellion at Dorset, in the West Country, with less than 100 men. The local militia crushed the rebels and captured Monmouth. The duke was hauled to London and executed. James II demanded a commission to root out any threat of uprising in West Country. George Jeffreys was made Chief Justice. He proved to be a butcher. The Jeffreys Commission was responsible for the infamous “Bloody Assizes” in which 480 men and women were executed, 260 whipped and fined, and another 850 banished to the colonies. So much for moderation and restraint. Soon the new Catholic King was hugely unpopular with the overwhelmingly Protestant English people. Regardless of the political turmoil, the Scientific Revolution marched forward. Isaac Newton published Principia in 1687 therein defining the Laws of Motion and Universal Gravitational force. Principia is now considered the seminal technical paper of the 17th century. Edmund Halley, a peer of Newton’s at the Royal Society, used the Newtonian laws to calculate and predict the course and timing of the comet that would make him famous – Halley’s Comet, which had blazed across the English night sky in 1682. The Bloodless Revolution of 1688 (or the Mostly Peaceful Invasion of 1688?) When I studied world history as a kid in America, it was common wisdom that the last time England was successfully invaded was William the Conqueror, sailing from Normandy, in 1066. William’s army defeated the Saxon army and killed King Harold at Hastings. Full stop. Then in 2009 my history book club sent 1688: The First Modern Revolution, by Steve Pincus. To my surprise, I learned that in 1688, the Dutch prince William of Orange sailed from Holland to take the English throne with more than 21,000 men, and a fleet twice the size of the Spanish Armada. Is that not a foreign invasion? Good question; answer – it depends. The 1688 invasion force included large numbers of English, Scottish, Welsh and Irish exiles. There was also a huge amount of financial support from inside Britain to support the invasion. William himself had a royal English wife (Mary was the Protestant daughter of James II) and also an English birth mother, so his deep connections to England made him a sort of Jack Englishman. So rather than seeing it as an invasion, it makes more sense to see it as part of a revolutionary movement from within Britain by military and civilian leaders who wanted to overthrow the regime of James II. The crown was offered to William of Orange and his wife Mary with the understanding that the British Parliament governed the affairs of England and determined the next monarchy. The crown was handed to William and Mary in 1689. The 1688 Revolution made a strong impression on the political future of America – that being an aversion to dynastic monarchies. Also the freedom of religion became an American core belief since so many of the English migrants to American had their lives disrupted by the persistent social unrest due to religious tensions in England.  William and Mary (1689-1702). William’s army marched on London and easily defeated the weak forces of James II. The ex-king fled to France with a large entourage. Parliament was free to make some long wanted changes. One good example was the creation of the Bank of England in 1694. The Brits used the Bank of Amsterdam as the successful model, with a few important differences: the Bank of England gave interest on deposits, whereas the Bank of Amsterdam didn’t. The other huge difference was that the Bank of England gave low-interest loans to manufacturers, so they could borrow money to get start-up capital to develop manufacturing. The Bank of Amsterdam didn’t do that either. A more modern financial system supporting Laissez-Faire, free-market capitalism was vital for England to ultimately surpass Holland as the leading economic power in Europe. Colonies of Delaware and New Jersey established 1701. Salem witch trials in Massachusetts 1692-1693; 14 women and 5 men found guilty of witchcraft and hanged. Modern historian and witch trial expert, Marilynne Roach writes, Women who did not conform to the norms of Puritan society were more likely to be the target of witch accusations, especially those who were unmarried or did not have children. Governor Phips defied the Puritan clergy and put an end to the disruptive witch trials. Witch trials were the last thing Phips needed with a war brewing in Maine with the hostile Abenaki tribe. The College of William and Mary established in Williamsburg, Virginia in 1693. W&M is the second oldest college in America and the first secular college. Harvard (estab. 1636) was more of a Bible college for theology students training for the clergy. While Harvard graduated preachers, W&M graduated three future American Presidents - Thomas Jefferson, James Monroe and John Tyler.  Anne (1702-1714) was the second daughter of James II and a Protestant like her sister Mary. She had children, but none survived. Duke of Marlborough commanded the English-Austrian army in the War of Spanish Succession, winning a series of major battles against France thus ending the Bourbon claim to unite with the Spanish throne. The balance of power in Europe was maintained for the ensuing ~90 years. The Anglo-Franco conflict on the continent spilled over into North America, and was known in the Colonies as Queen Anne’s War. The war was particularly harsh on the northern American colonies where Indian raiding parties, using New France (Canada and Acadia) as a base and armed with French weapons, butchered and captured thousands of Anglo-Saxon settlers. The hostile Indian tribes practiced a white slave trade on a wide scale. Queen Anne’s War is unique in that it was the last conflict in which the Anglo immigrants faced a true existential threat from the Indian tribes. Open war ended by peace treaty, but high tension remained between England and France, as well as, between the Colonists and warlike Indian tribes. England and Scotland united 1707. In 1703 Isaac Newton is elected President of the Royal Society. He would hold the position until his death in 1727. In 1704 Newton published another important scientific work, Opticks, based on his observations of refracting white light with a prism. In 1705 he is knighted by Queen Anne, thereafter, he is known as Sir Isaac Newton. House of Hanover  George I (1714-1727). So how did a 54 year old German-born prince, who did not speak English, become ruler over England, Scotland, Wales and Ireland? George was the great-grandson of James I. His mother, Sophia, was daughter of Elizabeth of Bohemia, the only daughter of James I. Sophia was “queen in waiting” after Anne, but died a few weeks before Anne. So the crown passed to her son, George. He never learned English, and left the running of the country to Robert Walpole and parliament. The Stuarts had a stronger legal claim to the throne, but they had fled to France in 1789 rather than face King William’s army. The Stuarts were welcomed in France by the French monarchy. More about the Stuarts later. Robert Walpole – first Prime Minister (PM). Held power for 21 years – 1721-1742. Walpole received the gift of 10 Downing Street in 1735 from George II, making it the permanent residence of the Prime Minister. Walpole was instrumental in creating a capitalist, conservative society; the fundamental aspects being: freedoms assured by rule of law, social stability, respect for private property, and capacity for growth. The catalyst for growth in the 18th century being the advent of the industrial revolution, hand-in-hand with advances in Western science and technology. George II (1727-1760) was only son of George I. He was more German than English, and wisely listened to his wife, Queen Caroline, to rely on Robert Walpole and William Pitt to run the country, same as his father had done. English territory in America expanded with the founding of Georgia in 1732. It was the last of the thirteen original American colonies established by England. In 1745 the Stuart’s went to war to reclaim the English throne. Prince Charles Edward, better known by the Scots as Bonnie Prince Charles, landed in Scotland with a few soldiers. He raised a small force of Highlanders and captured Edinburgh. King George’s son, the Duke of Cumberland, was sent to quell the rebellion. In April 1746 the two armies, 5,000 Scot Highlanders and 9,000 British regulars, faced off across the misty moor of Culloden. The Scots made a wild, frontal assault and were shot to pieces by Redcoat volley musketry and artillery. Charles panicked and fled the battlefield, and that was the bitter end for Stuart Catholic royal line to attain the English throne. English reprisals against the Scots were harsh, leading to a major increase in Scottish immigration to America. English-French rivalry and antagonism increased to the point that England declared war on France in 1756. The war was the first major conflict that spanned five continents, and could be actually be considered a “World War”.  William Pitt, the Earl of Chatham, came to power during the Seven Years War with France aka The French and Indian War (1756-1763). Pitt’s glory years were 1757-1762 when he was war leader and developed the strategy and picked the battlefield commanders that won the war. In 1757 the war spilled into India where a small English army under Robert Clive routed a much larger force of French and Bengal allies at Plassey. The rebellious Bengal Nabob, Suraj-ud-Daula, was captured and executed for murdering British prisoners in the “Black Hole of Calcutta”. A new British friendly Nabob replaced him. The Calcutta trading post and rule of Bengal was secured by the English for the next two hundred years. Pitt was spectacularly successful in 1759, the “Year of Victories”, in which the French were defeated on land and at sea on five continents: the capture of Quebec, and victories of Minden (Hanover Germany), Quiberon Bay (off coast of France), Guadeloupe (West Indies), Goree (Senegal, W Africa), and Lagos 1759 (off coast of Portugal). Under Pitt’s war leadership, and later as PM for two years 1766-1768, the British Empire greatly expanded, especially in North America with the addition of Canada, Acadia, and the Ohio Territory ceded by France to the British Empire by peace treaty. England was dominate on the high seas and created a highly lucrative trading empire.  George III (1760-1820). The grandson of George II developed into a solid King. This was the age of Revolution and legendary military leaders; George Washington, Arthur Wellesley (Duke of Wellington), Admiral Lord Nelson and, of course, the arch-nemesis of England, Napoleon Bonaparte. Relations with the American Colonies began to fracture mainly due to American anger over taxation – especially stamps and tea taxes. Many Whigs led by Edmund Burke supported the grievances of the American colonies and pleaded for peace. When war did break out he was still sympathetic for “American English”, but stopped short of endorsing Independence. In Burke’s view, “A Germanic king employing German boors and vassals was destroying the liberty of the colonists.” Rebellion and a shooting war started in Lexington and Concord, Massachusetts April 1775. Declaration of Independence 1776. Following a key American victory at Saratoga in 1777, the French King allied with the Americans against England. Revolutionary War ended soon after a major British defeat at Yorktown, Virginia in 1781. War weary Britain recognized American independence and signed a peace treaty ending hostilities. England ceded the Ohio Territory (aka the Northwest Territory) to the new United States.  French Revolution begins in 1789 with storming of Bastille. 1791 Louis XVI reign ends. France national convention declares France a Republic and the “Reign of Terror” begins. Louis XVI and Queen Marie Antoinette beheaded in 1793. The brutality of 1793 France stunned and frightened the British ruling class. The British were fast and effective in silencing radicals who believed a violent revolt was needed for England. The new French government ruthlessly purged the nobility from the military, and appointed new officers based on meritocracy and loyalty. War soon broke out in Europe and after a few years of constant war, Napoleon Bonaparte, age 28, was promoted to general and commanded an army in the field. But let’s not get sidetracked on old Boney, thus I will skip huge stretches of military history and leave it to you to discover on your own. Instead, my focus is on the (often overlooked) British civilian leadership which provided the war strategy, selected Generals and Admirals, and kept the war chest filled with gold. The two most able (non-military) leaders of the era were Castlereagh and PM Lord Liverpool. The two men led England through a life or death struggle, and never wavered until Napoleon was defeated and France was forced to sue for peace. Liverpool handled domestic policy and ran Parliament while leaving the main task of running the war to Castlereagh.  Viscount Castlereagh – A protégé of PM William Pitt, Castlereagh rose quickly up the ranks. At age 35 he was promoted to the key post of Secretary of War and Viceroy of India in 1804, just in time for a major rebellion in India. Castlereagh wisely gave command of the British Indian army to Arthur Wellesley. After a string of English battlefield victories, the rebellious Mahratta chieftains bent the knee and British rule was firmly established over the whole of the Indian subcontinent by 1805. Back in Europe, Castlereagh surveyed a bleak situation. Napoleon’s army crushed Austrian-Prussian forces in Italy, and occupied Holland; thereby, acquiring the Dutch fleet. France gathered an army on the channel coast and formed a new alliance with Spain. The Spanish put their large fleet under French command giving the French navy an advantage in the triple gun deck Ships-of-the-Line. The scattered French fleet began to gather at Cadiz, an Atlantic seaport in southern Spain. An English blockade fleet spied on the French at Cadiz and sent dispatches to London. Castlereagh was forced to prepare England for a possible French invasion; he ordered Lord Nelson to keep the French navy out of the English Channel, and if opportunity was presented destroy the enemy fleet. Imagine if you will, Admiral Nelson striding up the gangway of his flagship, Victory, with her black-and-yellow checkered gun decks and pipes singing and the drums beating and flags waving, and the redcoat marines at attention; it was to be his last voyage. When Nelson got word that French Admiral Villeneuve’s fleet had slipped into Cadiz harbor, he sailed his strong squadron south and gathered his forces just over the horizon from Cadiz. The British admiral kept a couple of spy ships roving about Cadiz while he summoned the fleet captains to a war council. Nelson was not surprised to learn his force of ships was outnumbered and out gunned by Villeneuve’s fleet. In fact Nelson had expected it, and had devised new tactics to spring upon the French. Nelson planned to abandon the traditional naval maneuver of lining up parallel to the enemy line and trading broadsides. Instead he proposed breaking his ships into two or three columns and striking the enemy line from the perpendicular. The columns would bust up the French line allowing the British captains to fight ship-to-ship in single combat; thereby, employing their superior seamanship and the magnificent English gun crews to the best effect. The British force offshore Cadiz waited in prey for over two weeks. On Oct 19 Villeneuve took the main French fleet back into the blue water, and steered south toward Gibraltar. The English fleet sailed in pursuit and closed with the French fleet. On October 21, 1805, off Cape Trafalgar, the British ships cleared the decks for battle and steered hard to port. As they bore down on a perpendicular course on the long line of French ships, Nelson sent his famed signal, “England expects that every man will do his duty.” Nelson’s flagship led one of the two columns of warships that knifed into the heart of the enemy fleet. The four hour slugging match began; the black-and-yellow hull of the Victory disappeared into a thick cloud of gunsmoke as ship after ship engaged. What happened that day is a Legend in naval history. The British victory at Trafalgar was decisive and saved England from any chance of invasion by the French. On the continent the French army continued to dominate. Napoleon was at the peak of his power and military skills in 1805-6. He surrounded and captured an entire Austrian army at Ulm. Two months later, at Austerlitz, he crushed a combined Austrian-Russian force, thus ending the Russo-Austrian alliance. While the French bargained over a peace treaty with the Czar and Austrians, the next war was brewing against Prussia. Prussian king Frederick rejected French demands and gathered a German army of over 200,000 men. Napoleon’s forces met the Prussians at Jena in October 1806, and destroyed the Prussians with a double envelopment. The Prussian king and queen barely escaped capture and fled to Berlin. England and France stalemated: the English army alone was no match for Napoleon on land while the Royal Navy ruled the blue water. Tactics changed to blockades and economic boycotts. In 1807 Napoleon turned his military against Spain, dethroned the Spanish king and installed his brother-in-law on the Spanish throne. The Spanish people rebelled against the harsh French rulers. The French next invaded Portugal, leading both Portugal and Spain to call for British support. In 1808 Castlereagh sensed that Napoleon had finally made a major mistake. He made a convincing argument to Parliament that France could not be defeated by seapower alone, making a Continental strategy essential. Castlereagh proposed sending a force to Portugal to fight the French invaders and support the Spanish rebels. Britain's financial strength and strong navy made it the only member of the Alliance able to operate on multiple fronts against France. Parliament approved sending a 15,000 man army to Portugal to launch the campaign that became known as the Peninsular War. The first troops arrived by sea near Lisbon in June 1808 commanded by Arthur Wellesley, who was by now a friend and protégé of Castlereagh. Wellesley was immediately successful and cleared the French out of Portugal. The British Parliament approved funds to triple the size of Wellesley’s army. In 1809 the Anglo-Spanish forces smashed the French at a major battle in Talavera, Spain – 75 miles from the capitol city of Madrid. Wellesley was awarded title and peerage of Baron and Viscount Wellington by King George III. Victory for England was a long way off, and for the next six years Wellington’s army continued fighting the French across Portugal, Spain and north into southern France. In the bigger picture, Spain was a sideshow to Napoleon who focused military plans and efforts on Russia. In 1812 Napoleon declared war on Russia and personally led a 600,000 man army across the Niemen River on June 24. Six months later in December 1812 a thoroughly defeated, starving and freezing French army crossed the Niemen and limped back into Poland. Less than 1 man out 6 made it back to France. Historian David Chandler summed up the situation: “It is quite possible that the French retreat from Moscow is the best-known military disaster in recorded human history. The scale is epic, the suffering incalculable, and the outcome catastrophic [for France and Napoleon].” Napoleon hurried back to Paris to build a new army and continue the two-front war.  PM Lord Liverpool reshuffled his ministry and appointed Castlereagh to Foreign Secretary in 1812. With Liverpool focused on domestic policy and running Parliament, Castlereagh, undistracted by the endless domestic politics, would become perhaps the greatest Foreign Secretary in all of British history. He would hold this position until his death in 1822. Castlereagh’s immediate challenge was to organize an alliance to destroy Napoleon, who had finally demonstrated by his Russia fiasco that he was not invincible. In this effort Castlereagh was very successful in engineering the Grand Alliance of 1813 – England partnered with Russia, Prussia and Austria, and finally brought Napoleon to heel with a great military victory at Leipzig and successful invasion of France. By mid-March 1814 Russian Cossacks were watering their horses in the Seine River. Paris fell and on March 31, 1814 Czar Alexander led the Russian army into Paris. The following month Napoleon abdicated and was exiled to a small island in the Mediterranean Sea (Elba). The House of Bourbon was restored to French throne. Castlereagh next offered the Americans generous terms to settle the War of 1812 which was unpopular in England. A peace treaty was approved at Ghent, Belgium in December 24, 1814. Due to slow communications, the final battle of the war was fought in New Orleans on Jan 8, 1815 and settled nothing except to propel Andrew Jackson, the victorious American general, to national fame. The War of 1812 is remembered in modern America for two songs: the national anthem, “The Star-Spangled Banner”, and “The Battle of New Orleans”. British general attitude toward US after the war was entirely friendly, and the two nations grew closer together.  With the guns silent, the Grand Alliance and the French convened the Congress of Vienna to hammer out a peace treaty including new borders in Europe. The Congress was interrupted in early 1815 when Napoleon made a dramatic return to power only to be defeated, once and for all time, at Waterloo by the British and Prussian armies on June 15-18, 1815. Wellington received the title Duke of Wellington for his success at Waterloo. A veteran of many battles, Waterloo was his last battle. The battle was also the only time Wellington faced Napoleon on the battlefield. Wellington would continue a long and distinguished career as a statesman, while Napoleon, like a caged lion, was left to patrol the rocky shores of St. Helena, one of the most remote islands on Earth. The Duke was quiet about Waterloo, prompting a few wags to opine that “Wellington had lost his fighting spirt due to the slaughter at Waterloo.” I doubt that. Wellington’s most famous comment about the great battle (comparing it to a ball) could be para-phased thusly, “I cannot explain it. You had to be there to see it.” His attitude perfectly displayed his upper-class distain for busy-body journalist and writers. My final comment on Napoleon Bonaparte - While Napoleon’s ambition and ruthlessness caused decades of killing and misery in Europe, he will always be remembered fondly in America for selling us the Louisiana Purchase of 1803 comprising over 827,000 square miles of land west of the Mississippi River. President Jefferson wisely agreed to pay less than 3 cent per acre to double the size of the United States. American negotiators were prepared to pay about $15 million for New Orleans alone, and were astonished when the vast territory was offered together with New Orleans.  With allied victory at Waterloo, the Congress of Vienna went back to business. Castlereagh was up against long odds to achieve a lasting peace treaty. He was most impressive in restraining the victorious Alliance from being too greedy in victory. He alone seemed to understand that stripping France of its dignity would set the stage for more wars. Castlereagh’s “Balance of Power” approach proved successful in keeping the peace in Europe for almost 100 years. Castlereagh continued as the British Foreign Secretary until his death by suicide at his Irish estate. He did not leave a note. His shocking death, of course, generated wild, imaginative theories as to why it happened that way. I consider most of the theories to be malicious garbage; he took his reason to the cold grave. To be generous, I consider the great man to be a belated casualty of war. He was buried in Westminster Abbey, a rare honor. Historian George Trevelyan argues: “In 1813 and 1814 Castlereagh played the key part in holding together an alliance of jealous, selfish, weak-kneed states and princes, by vigor of character and singleness of purpose that held Metternich [Austria Foreign Minister], the Czar, and the King of Prussia on the common track until the goal was reached. It is quite possible that, but for the lead taken by Castlereagh in the allied counsels, France would never have been reduced to her pre-war borders, nor Napoleon dethroned.” Well-deserved high praise indeed for an outstanding statesman who helped paved the way for decades of peace and prosperity in Europe, and helped make England the lead Lion of Europe. English Literature  Scene from the movie Persuasion (1995 release) Scene from the movie Persuasion (1995 release) Daniel Defoe was an English writer, trader, journalist, pamphleteer and spy. He is most famous for his novel Robinson Crusoe, published in 1719, which is claimed to be second only to the Bible in its number of translations. The famous novel inaugurated its own sub-genre of shipwreck fiction. Jane Austen (1775-1817) was a popular fiction writer during the Georgian Era. She is the indisputable queen of all time on the subject of husband-hunting. Her best sellers are still in print, and have made the jump to filmdom successfully. The BBC and Hollywood have both made multiple versions of Pride and Prejudice, Persuasion, Sense and Sensibility. The Wealth of Nations by Adam Smith – published in 1776 was a fundamental work on economics and was hugely influential on the economic policy of the English ruling class. Smith proposed natural laws of economics that formed the basis of Capitalism and helped propel England from a feudal to modern economy. Mary Shelley was an English novelist who wrote the Gothic novel Frankenstein in 1818, which is considered an early example of science fiction. Hollywood has made several films versions of the story. END OF PART ONE

0 Comments

|

AuthorWritten and edited by Ben Clark. Copyright 2016-2022. All rights reserved Archives

October 2021

|