|

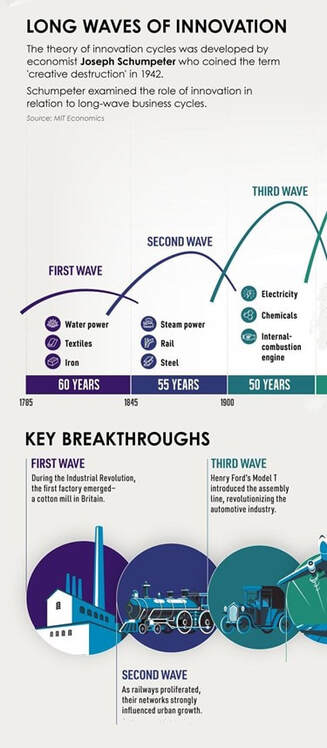

Part 2: Rule Britannia (1820 – 1910) Written by: Ben Clark As an American who has spent plenty of free time studying US history, beginning to study British history can be an intimidating task - there's just so much there compared to what we're used to. My solution is to divide and conquer, and use the monarchy timeline. This Part 2 essay extends from the death of King George III to death of King Edward VII – 90 years of rich British history, and includes the famed Victorian Era. What I condense to just a few pages is presented in books that take 500 pages to describe. This is, admittedly, a look from 30,000 feet, but from time to time I zoom in to treetop level for a more detailed review. During this era that I have sub-titled Rule Britannia, Europeans were incomparably successful at sending ships across oceans; on Round Trips. It’s true that some of the voyagers did not make it back, but over time the success rate steadily increased. Advances in ship building skills and navigation in Europe, combined with geographically precise maps, outpaced the rest of the globe by a huge measure. During the same time, the Europeans became most efficient at operating joint-stock companies and managing empires of unprecedented extension and degree of activity than anyone else. We have all heard the old cliché, “The sun never sets on the British Empire.” The same could have been said about the Spanish, Portuguese, French and Dutch empires during their glory days. By comparison, Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) lacked a single written language out of the thousands to tongues spoken in the vast area. They had no mathematical or musical notations, and inventions were scare to non-existent. The Sub-Saharan Africans had never seen a mechanical clock nor wheel until the European appeared. There were no roads, no law codes except the “Law of the Jungle”. Headhunting and cannibalism was practiced by many primitive African tribes, especially in the Congo. While it is fashionable today to condemn European Colonialism, SSA was clearly 500 years behind the Europeans BEFORE the first colony was established… Why? Alfred Crosby in his 1997 book, The Measure of Reality: Quantification and Western Society, 1250–1600, attempts to sum up this shocking intellectual gap with a practical recipe: Europe’s (the West) distinctive, and unmatched, accomplishment was to bring mathematics and measurement together and to hold them to the task of making sense of … reality. The Europeans increasingly shifted away from mysticism, superstitions and astrology for decision making. This shift made modern science, technology, and business practice possible, and was the driving force behind waves of innovation that swept over Europe. Due to an enlightened British government, the rule of law, respect for private property, and their unique form of free-market capitalism, the British proved to be the best at riding these early “long waves” of innovation to grow the largest, most profitable economy in the entire world. We begin Part 2 Rule Britannia with the continuation of |

AuthorWritten and edited by Ben Clark. Copyright 2016-2022. All rights reserved Archives

October 2021

|